It’s a difficult decision to cull our chickens, but it’s the economical thing to do and they make tasty freezer additions. The top birds to consider culling are excess roosters, non-productive hens, and slow-molting hens.

After processing culled birds, we can look forward to delicious chicken dinners, because chickens eliminated from home flocks tend to be more flavorful than supermarket birds. They generally don’t contain the antibiotics or growth hormones frequently given to commercially raised chickens, so they are healthier for us too.

But, it’s important to remember that the chickens in most home flocks are not like commercial meat birds sold in the supermarket, so the methods for preparing them are different. By understanding how chickens were traditionally prepared before commercial birds were developed, we can get great tasting results from our chickens too!

Fall Chicken Culling – Which Chickens?

EXCESS ROOSTERS

In fall, spring-hatched or purchased day-old chicks are maturing, and about half of these are typically roosters. Since most flocks only need a couple of roosters, and urban or suburban chicken-keepers may not want any, these young roosters are obvious choices for culling.

An Excess Buckeye Rooster (foreground) Is A Good Culling Choice

Today, folks often believe that roosters are not good for eating. However, our ancestors knew better and never let them go to waste. Young roosters, from both the egg breeds (such as Leghorns for Golden Buffs) and dual-purpose breeds, are delicious when prepared correctly. These birds are excellent for broiling, frying, or roasting (keep reading to learn how).

UNPRODUCTIVE HENS

Hens that are beyond egg-laying age are also prospects for fall culling. Some chicken-keepers become attached to hens and are willing to support them through old age; however, the frugal approach is to eliminate them before winter.

There are several indicators that can be used to identify nonlaying hens. One of the easiest is to look at the comb and wattle. Laying hens have vibrant-red combs and wattles, but these fade to pink when the hen quits laying.

Non-Laying Hen With Faded (Pink) Comb & Wattles

Another way to tell if a hen is laying is to look at her feet, beak, and vent. When hens are laying, they divert yellow color to their yolks. Once they stop laying, the yellow pigmentation will return to the vent, legs, and beak within 2 – 4 weeks.

If roosters are involved, another indicator is behavior. Roosters mate with laying hens, so if a hen always has a sleek, unruffled appearance, she may not be producing eggs.

Once a potential non-laying hen has been identified, it’s a good idea to confirm the condition before culling. This can be done by isolating the hen for a few days to see if she lays any eggs. Hens culled because they are unproductive are usually over a year old, and therefore are best used as stewing chickens.

SLOW MOLTERS

Since chickens molt in the fall, it’s also when slow molting chickens can be identified and culled. During molting, chickens stop or significantly slow down egg production, and a chicken can take from two to six months to molt. This egg production slowdown occurs because it takes the same nutrients to make eggs that it does to grow feathers.

Molting Chicken

Chickens that start molting late in fall usually molt quickly, whereas chickens that start early in fall generally take much longer to molt. Obviously, since they are not producing many eggs while molting, the better producers are those that start molting late and finish early. A chicken that molts for six months is much less productive than a chicken that molts in two months.

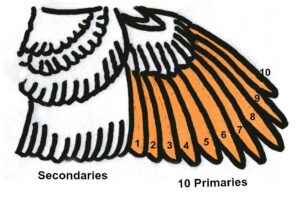

You can tell how long a chicken has been molting, and how much longer she’ll continue to molt, by looking at her primary feathers. Chickens have ten primary feathers on each wing – the orange-colored feathers shown below.

Feathered Chicken Wing Prior To Molting

When molting, a bird drops primaries approximately every two weeks, and each one takes about six weeks to regrow. A slow-molter will drop primaries one at a time and will take up to 24 weeks to re-feather. Fast-molters drop their primaries in groups instead of one-by-one and therefore return to production much faster.

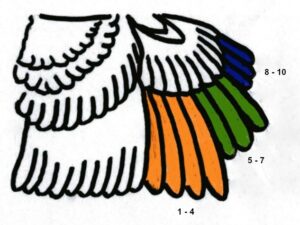

Slow Molting Chicken Primaries

The illustration above shows how a slow-molting chicken loses and regrows her feathers. In this illustration, primary #1 (in orange) was dropped and has fully regrown (so it’s six weeks old); primary #2 (in green) was dropped and is four weeks old; primary #3 (in red) was dropped and is two weeks old, and primary #4 (in blue) was dropped and just started regrowing.

This chicken is losing primaries one at a time, has been molting for six weeks and will continue for eighteen weeks more. It will take six more weeks for primary #4 to mature, eight more weeks for primary #5 to drop and mature, ten more weeks for #6 to drop and mature, and so on. That means it takes 24 weeks or about six months for a bird that molts this way to return to production.

Fast Molting Chicken Primaries

The final illustration above shows what happens with a faster molting bird. In this figure, primaries #1 – #4 (in orange) were dropped together and have fully regrown in six weeks. Primaries #5 – #7 (in green) were dropped, are regrowing, and are four weeks old. Primaries #8 – #10 (in blue) were dropped, are regrowing, and are two weeks old. This chicken is dropping primaries in groups, has been molting for six weeks, and will continue to molt for four more or a total of ten weeks.

Molting Chicken With Most Primaries Gone

Most chickens will complete molting somewhere between the above two examples; however, when you see a hen that’s dropped many primary feathers, you should keep her. She’s a better-producing chicken, while those that drop feathers slowly are candidates for culling. Chickens eliminated because of slow molting are best used as stewing chickens.

TRADITIONAL USES FOR BIRDS AFTER FALL CHICKEN CULLING

Today, most commercial chickens grown for supermarket have been bred to maximize throughput and minimize cost. They reach market size in a confined space within nine weeks and are promptly processed because losses from disease and health issues are high if they are kept longer.

One problem with birds grown quickly in tight spaces; however, is that they don’t develop much flavor. It takes time, an active bird, and a bird that has room to roam to become flavorful. Fortunately, these are all typical characteristics of chickens culled from home flocks.

Prior to the development of commercial birds (pre-1940), there were four chicken types that everyone recognized – the broiler, fryer, roaster, and stewing chicken. These types were based on when the birds were processed.

The traditional chicken was expected to produce meat and eggs for the table, and depending on the breed, the farmer would decide when best to process it as a broiler, roaster, fryer, or stewing bird. Although commercial supermarket birds are still called these names, there is no relationship to when they were processed. Traditionally,

Broilers were 7 to 12 weeks old and weighed 1 to 2 ½ lbs.

Fryers were 14 to 20 weeks old and weighed 2 ½ to 4 lbs.

Roasters were 5 to 12 months old and weighed 4 to 8 lbs

Anything older than a year was a stewing fowl

Broilers and fryers were often excess egg breed roosters because they couldn’t attain the carcass weight necessary for roasters, and roasters were typically excess roosters from meat or dual-purpose breeds. Stewing birds were hens or roosters being culled from the flock as older birds.

Roasted Fall Culled Chicken

Although all breeds can be culled young for fryers or broilers, in the past it was preferred to take the time to produce roasters because they were so tasty. Today, few remember that the traditional roasting chicken was a meat or dual-purpose breed rooster from fall chicken culling. The number of eggs produced by young hens made them too valuable for the table, particularly when there were roosters available.

AFTER PROCESSING

Chickens culled from home flocks usually don’t look much like “modern” supermarket birds after being processed. They tend to be longer, thinner, have longer legs, and have much smaller breasts than commercial chickens.

They are often about 50% dark meat and 50% white meat as opposed to the much higher ratio of white meat typical for commercial birds. And, because they are much older, they need to be handled and cooked differently for best results.

After processing and before freezing or cooking, it’s recommended that chickens be “aged” in the refrigerator to attain the best texture. Aging is typically from 24 hours to 3 days, depending on the age of the chicken before culling. At least 24 hours is generally recommended for roasters and at least 3 days for stewing chickens.

PREPARING CHICKENS AFTER FALL CULLING

When preparing chickens culled from the flock, it’s important to remember that older chickens have exercised much more than commercial birds. This increases the cooking time necessary to tenderize the muscles produced by the exercise. So, when cooking, undercooked dark meat or overcooked white meat can be a problem.

The traditional names for processed chickens also describe the best method for cooking them. Broilers, being young and tender, can be cooked quickly in the dry heat of a broiler or grill. Fryers are older and more flavorful, so they are usually cut into pieces to achieve both tender and properly cooked portions by frying.

Roasters are old enough to have developed significant flavor; but low temperatures and moist cooking methods are necessary. Graniteware roasters were developed to cook a chicken so that the meat would be both moist and tender.

Graniteware Chicken Roaster

For roasting, it’s recommended that the whole chicken be placed breast down in a small amount of water in the graniteware roaster. Then cooked at temperatures of 300° to 325°F for 30 minutes per pound. In addition to simply eating the roasted birds, I also like to use them in recipes like Heritage Chicken Pot Pie or Chicken Chili.

Chicken Pot Pie

Stewing chickens should be kept moist and the cooking temperature below 180°F for good results. Stewing can be done by covering the chicken with water in the pot and simmering for several hours until the meat is very tender and it falls off the bone. Both the shredded meat and cooking liquid can then be used for things like flavorful stews or chicken soup.

TAKE TIME FOR FALL CHICKEN CULLING

Culling can both reduce flock costs and stock your pantry. So, don’t forget to eliminate unproductive chickens in the fall. It’s not fun to cull and process birds from the home flock. However, you’ll benefit from more productive birds, better breeding stock, and scrumptious chicken dinners.

Miriam R. says

Good day!

Thanks for this article I had no idea on the specifics.

Very educational and appreciated.

Lesa says

Hi Miriam, Glad you found it helpful. Best, Lesa

Patrick says

Good stuff! Very interesting information about molting, too!

Tessa says

Slow molters – duh! Why didn’t I think of that?! I never even pay attention but that’s a great reason to cull unless it’s a particularly good mother hen. Thank you for the tip!

jan conwell says

Very thorough–and now I now how long to roast an older bird. Wondering if we should put liquid in the bottom? When I cook a pork shoulder I roast it for maybe 8 hours, but I put a couple of beers in the bottom of the roasting pan with the meat on a rack inside it.

Lesa says

Hi Jan, the post above identifies that you should put water in for roasting.

Janet Garman says

It is a tough decision to make but as you said, most of us can’t afford to keep feeding and housing unproductive chickens. Otherwise you would surely end up with a very large flock!

Mary says

Mine have been molting for the last few weeks so no eggs at the moment 🙁 My rooster is also molting and he has been quite territorial about food, changing from allowing the girls to eat first to giving them a good peck on the head and chasing them away from it if they try to eat before he has finished. I’ve never had a rooster before (he was sold as a pullet). Is that normal with roosters that are molting or has he made himself the most obvious choice for culling?

Lesa says

Hi Mary, I’ve not noticed that any of our roosters have acted this way when molting, but a roosters nutritional needs change quite significantly when molting. They don’t have the nutritional needs as the hens do for producing eggs all year, but then suddenly they do need lots of protein, etc. to regrow those feathers. I would wait it out, realizing that he’s probably acting differently because he suddenly has different nutritional needs. He’ll probably return to his hen-helping self, but if he doesn’t, you can always cull him later. 🙂

Jana says

My problem is how can we know which are laying and which hens are not laying? With 18 hens and 4 boxes I will get 6-11 eggs a day but I don’t know which hens are giving me those eggs. 🙂

Lesa says

Hi Jana, you can tell a hen that is producing eggs versus one that’s not by looking at their combs and vents. A producing hen will have a bright red comb and a moist and supple vent. A non-producing hen will have a dull pink comb and a dry-looking vent area. If you think that one’s not producing but want to make sure before culling, put her in a separate coop or pen and see if she produces any eggs.

Jana says

Thank you! Cull time this fall 🙂