Goat internal parasites (particularly worms) are one of the greatest challenges facing goat-keepers today. That’s

Internal goat parasites are particularly difficult to deal with because it’s hard to tell what kind and how many of them your goats have. For these reasons, it was once recommended that herd owners use an anthelmintic (dewormer) on a regular schedule to reduce internal parasite loads. However, this caused the parasites to become resistant to the anthelmintics and many of them are no longer effective in many parts of the country. Therefore, it’s now considered a bad practice to use anthelmintics for internal parasite control unless it’s absolutely necessary.

Parasitic Intestinal Worms

Parasitic intestinal worms harm goats by either feeding on or sucking blood from the intestinal lining. Those that feed on the intestinal lining reduce the goat’s ability to absorb nutrients while those that suck blood cause anemia. If the intestinal parasite load becomes too great, it will kill the goat. The most common intestinal worms that affect goats are described below in Table 1.

The most dangerous of these intestinal worms is the barberpole worm. It’s a voracious bloodsucker and multiplies rapidly so it can quickly destroy a goat. Barberpole worms prefer hot, moist conditions and are particularly prevalent in the Southeast of the United States. However, they are increasingly found in other regions of the US when hot weather and rain make conditions conducive to their survival.

Possible Barberpole Worm Egg

The nodular worm and whipworm are also blood sucking intestinal worms; however, they are usually present in small numbers. They are typically tolerated by mature goats. But, if barberpole worms are also present they compound the damage and can hasten death.

After the barberpole worm, the most common and damaging intestinal worms are the bankrupt worms. They feed on the intestinal lining which interferes with nutritional absorption and results in diarrhea if the worm load is heavy. This seldom causes death but can significantly decrease productivity (hence the name “bankrupt” worm).

|

Parasitic Intestinal Worms |

|||||

| Worm | Host Location | Blood Sucking? | Preferred Climate | Symptoms | Severity |

| Barberpole | Abomasum | Yes | Hot, moist regions – particularly Southeast US | Anemia,

Bottle Jaw |

Severe – Multiplies rapidly – Frequently deadly |

| Brown Stomach | Abomasum | No | Cool, wet – Temperate regions of US | Slow growth, Diarrhea | Rarely deadly – Poor production |

|

Bankrupt & Longneck Bankrupt |

Small Intestine | No | Cool, wet – Temperate regions of US | Slow growth, Diarrhea |

Rarely deadly – Poor production |

|

Nodular |

Large Intestine | Yes | Throughout US | Anemia |

Alone rarely deadly; however, compounds Barberpole |

|

Whip |

Large Intestine | Yes | Throughout US | Anemia |

Alone rarely deadly; however, compounds Barberpole |

| Tape | Small Intestine | No | Throughout US | Slow Growth |

Low – reduces productivity |

Table 1 – Parasitic Intestinal Worms

Other Goat Internal Parasites

The other intestinal parasites that commonly affect goats are listed in Table 2 along with the chemicals that are effective in treating them. The most dangerous of these are coccidia. During times of stress like weaning, they can overwhelm young goats that have not yet developed immunity and can be deadly.

Possible Coccidia Egg

Coccidiosis is a disease of the intestinal tract caused by the parasite coccidia. Coccidia are almost always present in the goat’s environment, and goats are generally infected with small numbers of the parasites that do very little damage. Adult goats usually have sufficiently robust immune systems to resist the coccidia, but young or sick goats are susceptible to developing an overload and disease.

The disease is spread through contact with infected feces, and it takes from 5 – 13 days after contact for the goat to exhibit the illness. The main indicator is diarrhea, which is followed by dehydration, weakness, and death if not treated. So, it’s a very serious disease for young goats and needs to be dealt with immediately. Older goats can have a problem with coccidia too, and stressful situations will often cause an outbreak. Bringing home a new strain of coccidia from a show or fair can result in diarrhea in both young and mature stock.

| Other Internal Parasites | |||||

| Parasite | Host Location | Treat With | Preferred Climate | Symptoms | Severity |

| Coccidia | Intestinal Lining | Baycox, Corid | Over-crowded Conditions | Diarrhea, Weight Loss | Severe – can quickly cause death in young stock |

| Liver Fluke | Liver | Albendazole, Ivomec Plus | Swampy Areas | Weight Loss | Moderate – can be deadly |

| Lung-worms | Lung | Albendazole, Fenbendazole, Ivermectin | Cool, wet climates | Chronic Cough | Moderate – can be deadly |

| Menin-geal worm | Spinal Cord & Brain | Ivermectin | Whitetail Deer | Paralysis, Weak Legs, Blindness | Severe – rate of infection is low but once infected often deadly |

Table 2 – Other Internal Parasites

Detecting Internal Parasites

All goats have some level of internal parasitism but if the parasite load becomes overwhelming then treatment to reduce the load needs to be performed. There are several methods for determining whether treatment should be started including monitoring appearance, dropping consistency, mucous membrane coloration, and fecal sampling.

Weight loss, clumpy droppings, diarrhea, rough coat, and listlessness are all indicators that the parasite load is overwhelming a goat. If diarrhea is involved in young goats, it’s typically an indicator of coccidia and treatment is necessary once the cause is confirmed. In older goats, it’s usually an indication of non-blood sucking intestinal worms. Your veterinarian can analyze a fecal sample, identify the parasite, and recommend treatment.

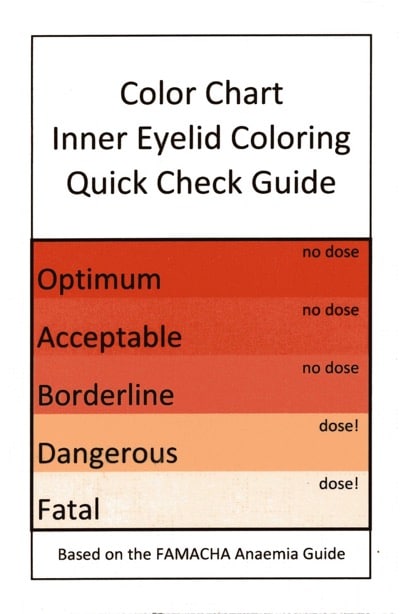

Since the blood-sucking worms (primarily barberpole) are so dangerous, a system for evaluating the need for treatment without relying on laboratory analysis called FAMACHA was developed in South Africa. To use this system, the coloration of the goat’s lower inner eyelid is compared to a FAMACHA color chart (see Figure 1) and those goats exhibiting coloration in the dangerous or fatal zone are treated with anthelmintics. Another indicator of a dangerous level of blood-sucking worms is the development of bottle jaw and any goat with bottle jaw should be immediately treated.

This system has been widely adopted in the United States and has helped to slow the development of super worms that are resistant to the dewormers. FAMACHA training classes are regularly held around the country and information on them can be found through the American Consortium for Small Ruminant Parasite Control website (https://www.wormx.info/resources).

Figure 1 – Famacha Chart

Deworming*

For many years, goat internal parasites were controlled by regularly administering the chemical dewormers listed in Table 3. However, many worms (and particularly the barberpole worm) have developed resistance to all the dewormers currently approved in the US.

Resistance develops when dewormers are underdosed and rotated too frequently thereby promoting the survival of more resistant worms. These resistant worms eventually develop into super worms that can’t be controlled with any of the available dewormers. Once resistance to a dewormer has developed on a property, that dewormer will no longer be effective.

| Dewormers – Anthelmintics | |||

| Class | Anthelmintic | Commercial

Name |

Approved For Goat Use (in US)? |

| Benzimidazole | Fenbendazole | Safeguard

Panacure |

Yes (Drench) Yes (Drench) |

| Benzimidazole | Albendazole | Valbazen | No |

| Imidazothiasole | Levamisole | Prohibit

Levasol Tramisol |

No |

| Imidazothiasole | Morantel Tartrate | Rumatel | Yes (Feed) |

| Macrocyclic Lactone | Ivermectin | Ivomec | No |

| Macrocyclic Lactone | Moxidectin | Cydectin | No |

| Amino Acetonitrile | Monetantel | Zolvix | Not Yet Approved in US |

Table 3 – Common Dewormers

Since anthelmintic resistant super worms are a reality, it’s critical to use the chemical dewormers very carefully. If a dewormer is still effective on your property, that effectiveness should be conserved so it’s available when really needed. Other techniques for controlling internal parasites should also be implemented to conserve the efficacy of dewormers.

The first step in properly using the chemical dewormers is to determine which are still effective at your location. This can be determined by having a fecal egg count reduction test (FECRT) or a larval development assay (DrenchRite) performed.

Once you know which dewormers are effective, do not routinely deworm the entire herd, only deworm those goats that need it. Also, be sure not to underdose, so as many worms as possible are eliminated. Don’t allow some to survive and become resistant. The proper dosages of the various chemical dewormers for goats can be found at the link here1. Note that the only anthelmintics approved for use on goats are fenbendazole and morantel tartrate. Using any of the other commonly available dewormers constitutes extra-label use.

It’s important to properly administer the dewormer too. All of the chemical dewormers (except Morantel Tartrate which is administered in feed) should be delivered orally over the back of the tongue using a drenching tool. Another recent recommendation is to withhold feed for 12 hours prior to deworming to slow the movement of the anthelmintic through the digestive system and allow it to contact and kill as many worms as possible.

Drenching Guns

Because the resistance to dewormers has become so great, the latest recommendations are to use two or three classes of dewormers in combination to obtain the greatest efficacy possible. Other countries have products available where the multiple classes of dewormers have been premixed so only one product needs to be purchased and administered. However, none of these products are available yet in the US.

When administering multiple classes of dewormers, they should not be mixed in the same syringe. Instead, they should be administered separately, but one right after the other. When being used in combination, the dewormers should all be used at the full recommended dosage. Any safety precautions that are recommended for a single dewormer are also applicable when dewormers are used in combination; however, there are not any known additional risks when using dewormers in combination.

When introducing a new goat, remember that it’s very important to deworm the goat and quarantine it. The goal is to kill all worms while the goat is in quarantine so that your herd is not exposed to any new parasite strains or anthelmintic-resistant worms.

Treatment for coccidia is handled differently than treatment for the other internal parasites. Most veterinarians in the US will prescribe Corid (amprolium) at 1 cc/20 lbs. for five days or alternatively Albon (sulfadimethoxine) for five days to treat it.

Corid is a Vitamin B inhibitor, so when using Corid the goats should also be given Vitamin B. Also, Corid isn’t effective against all stages (there are two stages of life for the parasite) of coccidia, so five days of treatment may not be enough.

As an alternative (but not approved for use in the US), many breeders are now using a drug that was developed to combat both stages of coccidia and that is given in just one dose (and in the case of an outbreak may be repeated in 10 days) called Toltrazuril (Baycox). It can be found here. The dosage we were advised to use was 1 cc/5 lbs orally as a drench. It certainly is easier to give one dose of Baycox as opposed to Corid and Vitamin B to multiple goats with diarrhea every day.

In addition to administering the drugs above, it’s important to keep all the goats showing signs of coccidia hydrated. If the signs of an outbreak are caught quickly, the goats are treated promptly, and kept hydrated, then they usually recover fully within a few days.

Additional Strategies for Controlling Internal Parasites

There are a number of other strategies that should be considered for use in conjunction with chemical dewormers to help control internal parasites. Since dewormers are becoming ineffective, incorporating these strategies is becoming critical for successful goat keeping in many areas.

The first of these strategies is selecting parasite resistant stock. Try to purchase your first goats from a breeder that is actively selecting for parasite resistance. Then, as you observe your goats and check whether treatment is necessary, make sure to record which goats need treatment as well as those that don’t. Over time, it’s likely that you’ll notice that some goats seem naturally robust and never seem to get “wormy” while others need to be treated frequently. Remove the goats that need frequent treatment from your herd and select young stock only from parents that are resistant to parasites.

Another strategy is to utilize goats preference for wooded browse over a pasture. Goats usually get worms by ingesting larvae that have hatched out of eggs in goat droppings. However, these larvae can only travel a few inches up a blade of grass or leaf. Goats prefer to reach up and browse rather than reach down and graze, so if they are kept in areas with wooded browse rather than pasture they tend to ingest fewer worm larvae because they are not eating from the ground. For this reason, it’s also better to feed hay from overhead bins rather than feeding hay from the ground.

Copper bolusing has also been shown to be an effective strategy for controlling barberpole worms. Copper bolusing has been used as a method to supplement copper in livestock for years in copper-deficient areas. Recent findings have shown that it also helps eliminate significant numbers of barberpole worms.

Yet another strategy that is gaining popularity is feeding goats condensed tannin-containing forages. So far, testing has only been conducted on one condensed tannin containing forage (sericea lespedeza); however, it has been shown to reduce both worm loads and coccidia in goats.

*The control of internal parasites in goats is a complex and rapidly changing topic. In-depth information and the latest recommendations for dealing with internal parasites can be found at the American Consortium for Small Ruminant Parasite Control website (https://www.wormx.info/resources).

1 Dewormer chart for goats; Ray Kaplan, DVM, Ph.D., University of Georgia [updated 2014]

Anna says

If coccidia is moderately present in an adult goats fecal test are they typically treated? Or only when young? Thanks!

Lesa says

Hi Anna,

Coccidia are nearly always present but adult goats normally have strong enough immune systems so that they don’t get out of control. So yes they are normally not treated.

Amanda says

Great information, thank you!

A microscope is at the top of my Christmas wish list this year so that I could start better diagnosing what parasites are causing issues in our herd, without having to call a vet out. I got some crazy side-eye from my husband an parents, but when I explained just 4 fecal samples processed at the vet would pay for the cost of the microscope, they “got” it ha ha. Plus, I’m looking forward to hopefully learning enough to share it with our 4-H kids so they can learn as well.

Lesa says

Hi Amanda, yes a microscope makes it a lot easier to figure out what’s going on in your herd. I think we got one after about a year of owning goats, taking in fecal samples and waiting on the vet gets old fast 🙂 Hope Santa is good to you and comes through with that microscope!